Saleem Asmi, Nov. 29, 1934 – Oct. 30, 2020

First published in The News on Sunday, Nov. 8, 2020. Reposted here with more photos.

By Beena Sarwar

His old friend S. M. Shahid termed Saleem Asmi a ‘Marxist Sufi’ in his compilation of biographical essays, ‘Living Souls: Memories’. Asmi Sahib would typically brush aside the accolades that came his way, not because he didn’t appreciate himself but because he had no false pride, false humility, or a shred of hypocrisy.

I can imagine his chuckle at the couplet by his favourite poet initially chosen by family and friends to inscribe on his gravestone:

Ye masaail-e-tassawuf, ye tera byan Ghalib

Tujhey hum vali samajhtalay jo na baada khwar hota

The way you talk of philosophy Ghalib, the mystical way you explain it

You would have been considered a saint yourself, had your drinking been less.

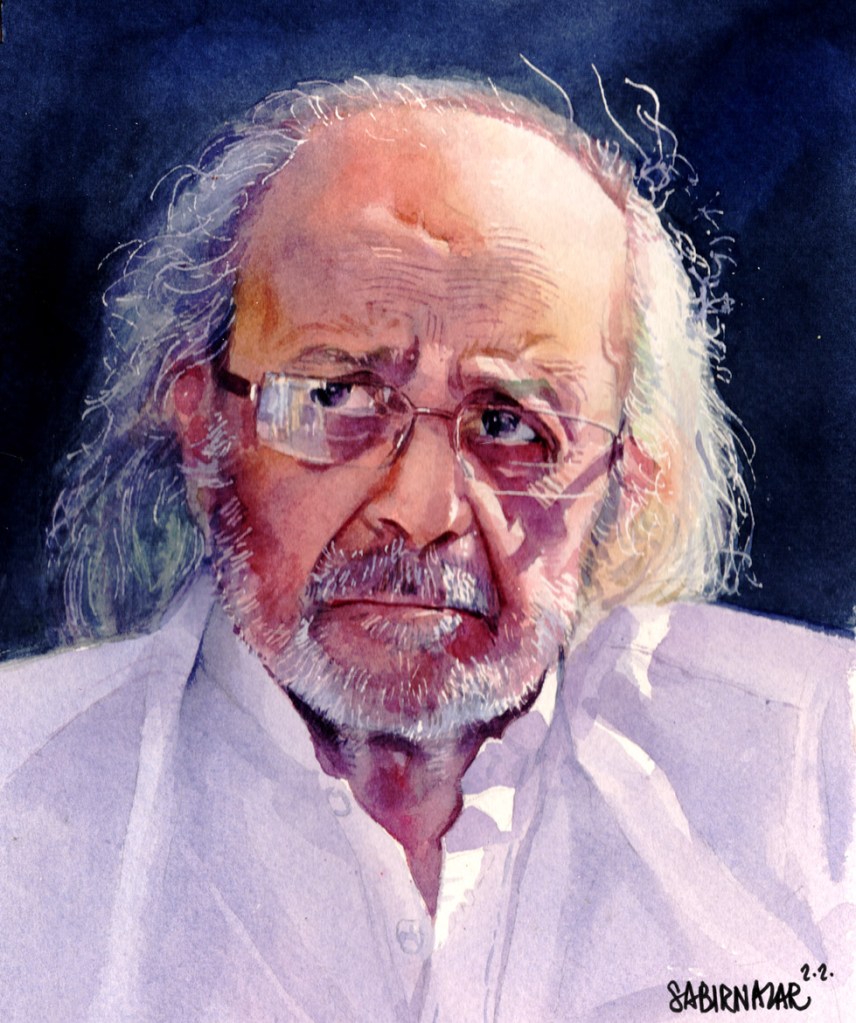

His handlebar moustache and ferocious beard (nattily trimmed in later life), long hair curling over the back of his collar, often in casual t-shirts and jeans — when I first met him in the 1990s Asmi Sahib looked more like the rebellious artist he was at heart than a newspaper editor. His concession to conformity was ‘safari suits’ at work.

Unlike my father’s other friends, he was never “uncle” or “chacha” to me. Just Asmi Sahib. I never heard anyone call him by his first names, Syed Fazle Saleem. I had moved from Karachi to Lahore and was starting life as a journalist when Asmi Sahib reappeared in Pakistan after years of self-exile away from Gen. Zia’s military regime.

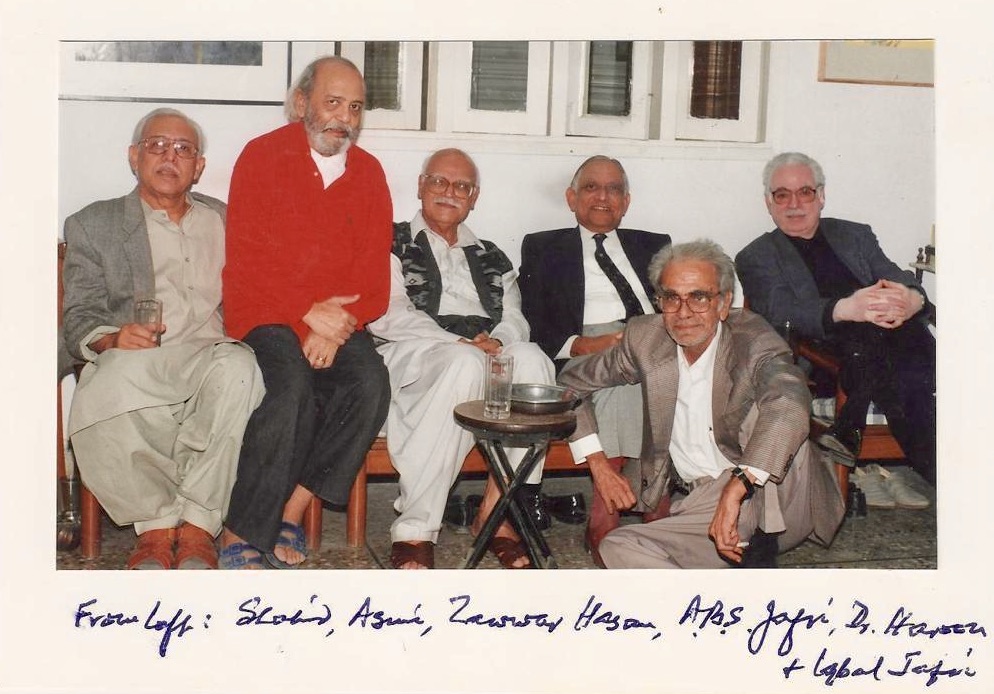

Our friend Anis Haroon describes how, as she and her husband Dr Haroon Ahmed were leaving artist Bashir Mirza’s place one night, they heard someone coming up the stairs. A stranger.

Then ensued a ‘tamasha’ – a spectacle. Haroon and the newcomer greeted each other delightedly and fell into each other’s arms. Anis remembers her consternation – this unknown man with big ‘wadera’ (landlord) moustaches, being greeted by her husband like an old friend.

“This is Asmi, one of our DSF comrades”, said Dr Haroon. Asmi, working in Dubai as editor of Khaleej Times, had returned to Pakistan in 1988. Winds of change were blowing aside the darkness cast by the Zia years. A new dawn was flickering on the horizon – that elusive dawn we never quite attain, as Faiz Ahmed Faiz has eloquently said.

It took Anis some time to warm to this new old friend who looked a bit like a bandit. But under the gruff exterior was a man with immense wit and charm, open-heartedness, love for art and music, and passion for politics and life. The Haroons reconnected him with my father, Dr M. Sarwar, who had led DSF, the Democratic Students Federation in the 1950s.

Asmi took quiet pride in terming himself as a worker, not a leader – although he was the DSF President at SM College. After my father passed away in 2009, Asmi Sahib was one of the key DSF activists we interviewed for the documentary film, “Aur Niklenge Ushshaq Ke Qafley” – There Will Be More Caravans of Passion, documenting DSF).

It was Asmi who suggested the title, borrowed from Faiz’s immortal ‘Hum Jo Tareek Rahon Mein Maare Gae (we who were killed in the dark lanes).

The right-wing students would generate propaganda against activists of the short-lived but powerful nationwide movement that peaked in 1953-54, labelling them as Communists. “I never cared if anyone called me that”, said Asmi, half-smile lurking behind the serious exterior, characteristic glint in his eyes.

We connected in many ways, over many issues, and through many friends. He was ‘Asmi Nana’ to my daughter. In fact, he had a special relationship with children and young people in general. Never patronising or condescending, a man of few words, characterised by humility and compassion.

Asmi dignified his domestic employees with the same respect he gave children and his peers. They reciprocated in the care and devotion with which they looked after him, particularly as he became immobile and confined to a wheelchair. He bore his ailments and personal discomforts stoically, calmly, even serenely. Never a word of complaint.

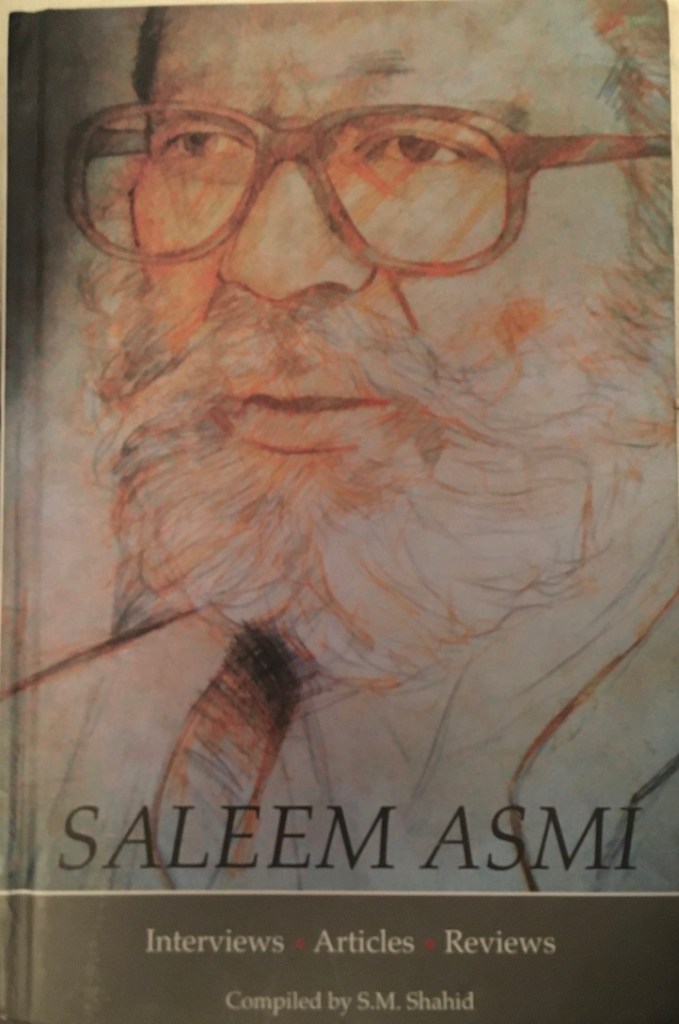

As editor, he never tried to ‘play boss’, attested journalist Muhammad Ali Siddiqui at the 2012 launch of ‘Saleem Asmi –Interviews, Articles, Reviews’, a book lovingly compiled by S.M. Shahid. (What friends do: Compilation of Saleem Asmi’s writings published, The Express Tribune). Valuable read for all journalists and anyone interested in Pakistani politics, art, music and culture (Our mutual friend Dr Naazir Mahmud describes Asmi Sahib’s engagement with these issues in his remembrance: What we learn from Saleem Asmi).

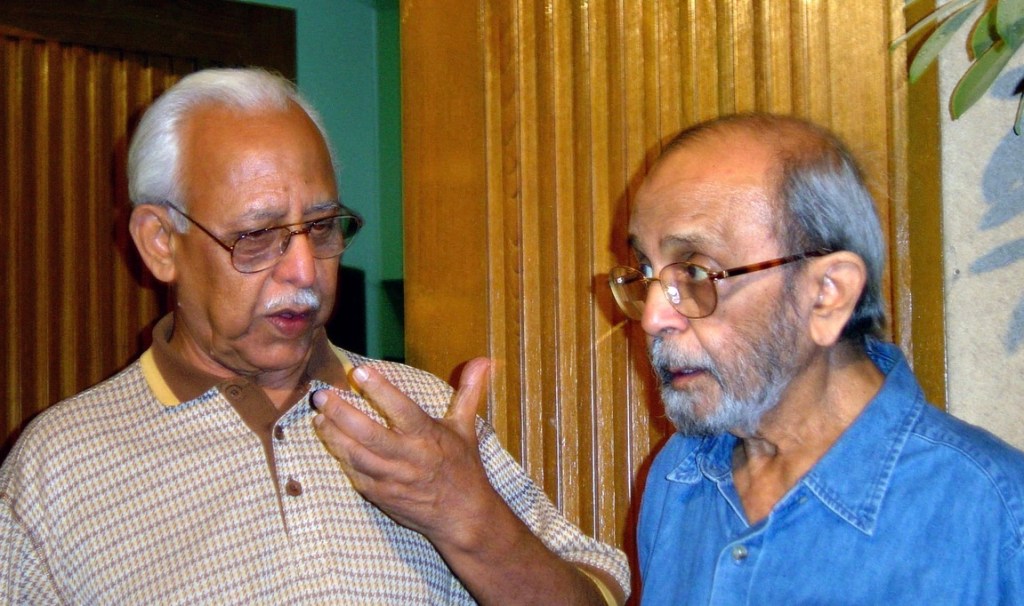

Asmi started his journalistic career as a trainee sub-editor with The Times of Karachi after obtaining a Masters in English literature from Karachi University. In the early 1960s, he was in Lahore working with the Civil Military Gazette, then joined The Pakistan Times. It was in Lahore that he and I. A. Rehman first met.

Rehman, a few years older, had been with PT since 1951. He recalls that Asmi left PT for a brief stint with PIA Public relations, but soon returned to journalism, joining PT’s ‘Pindi office.

Soon after Gen. Ziaul Haq’s military coup in 1977, Asmi was among the journalists arrested for defying the military authorities.

When daily The Muslim was launched in Islamabad in 1978, Asmi was among the launch team, as news editor with editor A. T. Chaudhry. Asmi is credited with designing The Muslim’s first layout, an achievement stemming from meticulous research as I.A. Rehman has outlined in his moving tribute, The end of spring (Dawn, Nov 5, 2020).

It was during this time that their friendship deepened. Rehman, working with NAFDEC, the now defunct National Film Development Corporation, and back in Lahore, would frequently fly to the capital. Asmi would pick him up in his little ‘foxy’, the Volkswagen Beetle. “He’d drive me around all day, then drop me back to the airport”, reminisced Rehman Sahib when we spoke recently. (Rehman Sahib had earlier lived in Islamabad with his family for three years between 1975-78. Those days Asmi Sahib would commute on a Vespa scooter, remembers Rehman Sahib’s son Asha’ar, now editor Dawn Lahore).

Then, under pressure from the military regime, The Muslim fired about a hundred workers and journalists. The army sent in troops to turn them out. Secretary General Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists Nasir Zaidi, president of the Muslim Union at the time (among the journalists to be flogged in 1978) remembers Asmi being on the streets protesting along with the workers.

Asmi was among the journalists who courted arrest in protest at harsh censorship and closure of papers including the Urdu daily Musawat. A Lahore military court sentenced them to hard labour. Asmi served the sentence in Multan jail along with others, including Nasir Malik.

When Malik’s hand started bleeding while weaving ‘baan’, he was tempted to show it to the jailor and get sent to hospital. Asmi shot down the idea with his characteristic forthrightness: “Senior journalists have gone to jail and done hard labour, never sought compromise. What kind of conviction do you have that this injury has scared you?” (جیل میں مشقت کرنے والا سرکش دانشور صحافی، سلیم عاصمی کُوچ کرگیا – BBC News اردو )

After his release a month or so later, Asmi joined the Khaleej Times. Today, “we can still picture him, with reading glasses balanced on his nose, poring over page bromides at midnight before they went to the cameras”, write Neville Parker and Joseph Nellary/Dubai (Colleagues mourn death of veteran Pakistani editor Saleem Asmi, November 2, 2020).

As Editor Dawn, one of Asmi’s most significant and lasting contributions was introducing sections that made it a more complete paper – weekly supplements for culture, art, books. He also took the then unprecedented step of publishing a major news story by a non-staffer – Hamid Mir’s interview of Osama Bin Laden in November 2001 that Mir’s own paper, Ausaf, was reluctant to publish.

Despite pressure from the Musharraf regime, as editor Dawn Asmi went ahead with the interview, as Hamid Mir tweeted:

Asmi’s retirement in 2003 – he was rumoured to have been pushed out because his decisions caused discomfort in high places, something he never spoke about – coincided with the rise of social media. He became an avid iPad user. His thousand Facebook friends include dozens of young journalists and artists whom he nurtured, mentored and guided.

He also used the platform to promote causes close to his heart – human rights, social justice, even sensitive issues like Balochistan and right-wing radicalism. One such post led to his account being briefly suspended in 2015.

He flirted briefly with Twitter but didn’t go beyond a few pithy tweets and some responses, before losing his password and dropping it. But his bio says it all: “Marxist Feminist Animal Lover”.

After leaving Dawn, Asmi became active with the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan. HRCP founder Asma Jahangir had recruited I.A. Rehman and Aziz Siddiqui as co-directors. He served as the elected co-Chairperson HRCP Sindh and set up the Karachi office.

As I learnt only after his passing, he also began to indulge in his passion for art, mounting found objects like rocks, stones and driftwood. There was even an exhibition at Anis and Dr Haroon’s home. S.M. Shahid compiled the images in a coffee table book.

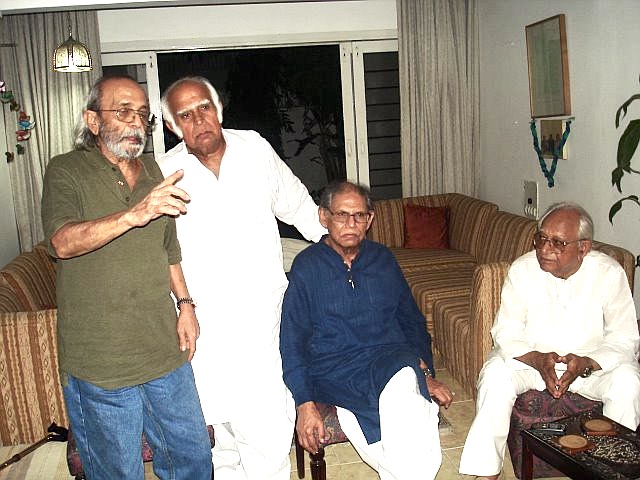

Coincidentally, Zohra Yusuf, my first editor when I was an intern at The Star in 1982 and later also a co-Chairperson HRCP Sindh, became Asmi Sahib’s neighbour when she and her family moved in next to his ground floor flat in Frere Town near my parent’s place. Ceramic plates and a veritable forest of potted plants on their joint outside wall greeted visitors, a welcoming hub for common friends.

Asmi Sahib’s flat particularly was a hangout for journalists, artists, music and culture lovers. I.A. Rehman always made it a point to spend his evenings there on visits to Karachi. Zohra would join, treasuring the conversation and company. Picturing these icons of journalism and human rights activism together is itself an inspiring thought.

Rest in power Asmi Sahib. Pakistan is poorer without you.

Nov. 15: Updated to add information about Asmi Sahib’s 1970s Vespa scooter and artwork.

(ends)

Filed under: Obituary, Progressive politics, Student politics | Tagged: Asma Jahangir, Dawn, Democratic Students Federation, Dr Haroon Ahmed, DSF, HRCP, journalism, Khaleej Times, Pakistan, S M Shahid, Saleem Asmi, zohra yusuf |

Will miss him a lot. I was lucky to have spent some time with him the past few years,

LikeLike

Thanks Moeen. I’m not surprised – he was such an art lover. I think I saw some of your work in his place also?

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Dr M. Sarwar (1930-2009).

LikeLike

[…] A quiet warrior slips into the night: Bidding farewell to journalist Saleem Asmi (1934 – 2020) […]

LikeLike