An exciting update to the story of Jagannath Azad’s tarana for Pakistan is that the talented young Shahvaar Ali Khan in Lahore has composed and sung it. Shahvaar released the song, that he has titled ‘Azad ki dua‘, on Aug 14 on Youtube. It is also exciting that Radio Pakistan agreed to broadcast it, every three hours on its nine FM 101 channels.

Scroll further below for my essay, Pakistan’s ‘lost’ anthem, published in Fountain Ink a few days ago

Here’s Shahvaar’s composition with the beautiful video he put together at record speed:

Below, my story of how this came about, in Aman ki Asha (Aug 15, 2012):

India-Pakistan peace: ‘Azad ki dua’

A young musician revives Jagannath Azad’s 65-year old national song for Pakistan

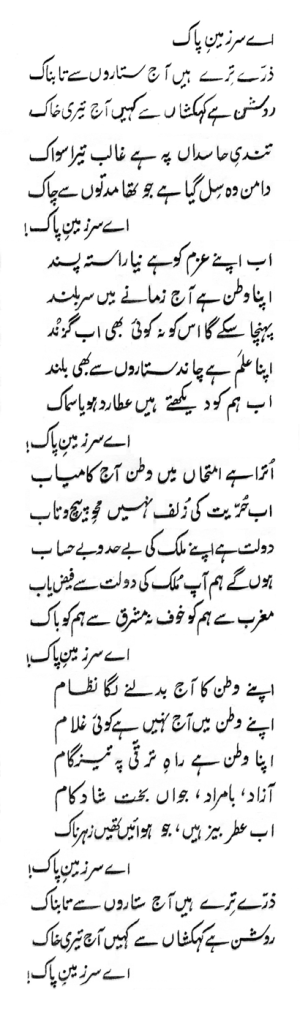

Ae sarzameene pak

Zarray teray haen aaj sitaaron se taabnaak

Roshan hai kehkashaan se kaheen aaj teri khaak

Ae sarzameene pak

(O pure land / The stars illuminate each particle of yours / Your very dust is today brighter than a rainbow / O pure land)

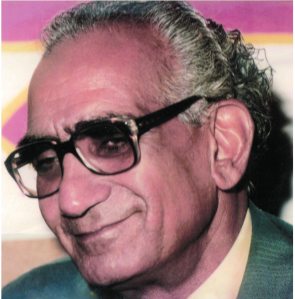

Sixty-five years after it was written, young Lahori musician and peacenik Shahvaar Ali Khan has composed and sung the poem penned by another Lahori, the poet Jagannath Azad on the eve of Pakistan’s independence in August 1947.

Khan’s melodic tune and mellifluous voice, coupled with Azad’s simple lyrics, make ‘Azad ki dua’ (as Khan has titled it), a hummable tune that will be a moving addition to Pakistan’s repertoire of national songs. The composer has treated the poem musically as “a contemporary soft tune, an emotional love/prayer song for Pakistan from Azad” as he puts it, with a chorus adding to its depth.

Shahvaar Ali Khan is known on both sides of the border for his songs starting with his first single “No Saazish No Jang” (Geo TV and Aag), followed by ‘Filmein Shilmein‘ in Akshay Kumar and John Abraham’s ‘Desi Boyz’. His third single was a tribute to the great Mehdi Hassan, ‘Jab Koi Pyaar Se Bulayga’.

We had been interacting since he was a student at Trinity College in Connecticut, majoring in Economics and International Studies. He contacted me with reference of his adviser, the well-known progressive historian Vijay Prashad. When I became intrigued with Azad’s Pakistan tarana a few years ago, Shahvaar was keenly interested in my research. A few days ago, when I suggested he compose and sing the poem in time for Independence Day, his enthusiasm for the idea was reflected in the speed with which he moved, completing the musical score in just a day. He has also done complete melodic justice to the stature of Azad’s lyrics and love for Pakistan.

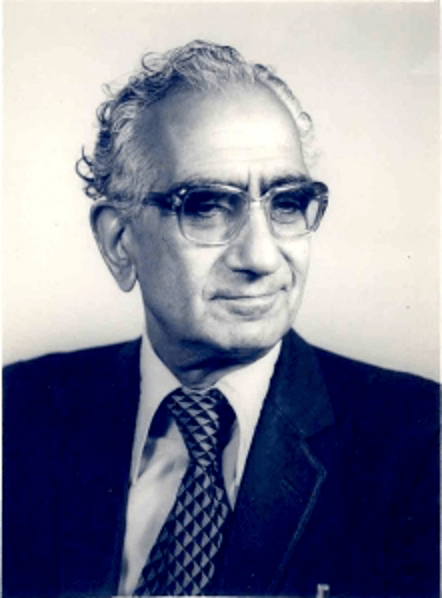

Born in Isakhel, Mianwali, in 1918 Jagannath Azad was the son of the poet Tilok Chand Mehroom who was also an acclaimed naat khwan. Azad also became a well-known Urdu poet. An acknowledged scholar of ‘Iqbaliat’ (poetry and prose of Allama Mohammad Iqbal), he left Pakistan with great reluctance some months after partition. He returned for several mushairas, happy to be back, warmly received, but pained to be coming ‘home’ as a ‘guest’.

Azad always maintained that he wrote “Ae Sarzameen-e-Pak” at the behest of Pakistan’s founder Quaid-e-Azam M.A. Jinnah, and mentioned its broadcast on Radio Pakistan on Aug 14, 1947 in several places. There are some alive who recall hearing the broadcast.

However, there is no record available of the Quaid-e-Azam’s request to Azad, or of the radio broadcast – not surprising given the ad hoc nature of decision-making and the lack of recording facilities at the time. Azad’s ‘tarana’ was never ‘officially’ adopted as Pakistan’s national anthem. It was discontinued soon after the demise of the Quaid-e-Azam. A National Anthem Committee was formed in December 1948 but it was not until 1954 that Hafeez Jalandri’s lyrics were formally adopted as Pakistan’s official national anthem.

A passionate proponent of good relations and peace between India and Pakistan, Azad’s last wish, as he told Kashmiri journalist Luv Puri in an interview shortly before passing away in 2004, was to pen a “song of peace” that would be common to both countries and sung by millions of Indians and Pakistanis.

“It is my wish that one day the people of the two countries will sing the songs of love instead of hatred,” he told Puri.

Setting aside the controversy of whether or not Azad’s poem was Pakistan’s first national anthem, the stirring Urdu poem and its modern composition have the potential to become another national song for Pakistan, like ‘Sohni Dharti’ or ‘Dil Dil Pakistan’. It is certainly something that Pakistanis should know about.

As Azad said at an Indo-Pak mushaira honouring Qateel Shifai in Dubai, 1992:

Siyasat ney jo khenchi hain hadein qayam rahein beshak,

Dilon ki hadd-e-faasil ko mitaa dene ka waqt ayaa

(Let the lines drawn by politics remain intact

It is time to erase the distance between hearts)

– Beena Sarwar

The essay below was initially published in The Fountain Ink, August 07, 2012 (http://fountainink.in/?p=2397)

Pakistan’s ‘lost’ anthem

How poet Jagan Nath Azad’s national anthem for Pakistan—its first—was quickly replaced and forgotten

By Beena Sarwar

Like most Pakistani children I grew up singing the country’s national anthem every morning at school assembly. Our rotund music teacher Mrs Lobo would pound out the tune out on the school piano as rows of uniformed boys and girls obediently mouthed the words, “Pak sar zameen shaad baad…”, Blessed be the sacred land. Some jokers would strike a discordant note to make their classmates laugh. I doubt any of us ever thought about the meaning of the heavily Persianised words.

We all knew that the lyrics of this anthem were written by the late poet Hafiz Jallandari several years after the country was born. Until then, there was no anthem. Or so we thought.

It wasn’t until fairly recently that I discovered, from a most unexpected source, that there was an earlier anthem – sanctioned by the country’s founder, broadcast by Radio Pakistan when the country gained independence, but not adopted ‘officially’.

It was August 2009. I was returning to Karachi from Lahore, about an hour and a half long flight. Bored, I reached into the seat pocket before me to pull out Humsafar, Pakistan International Airlines’ glossy bi-monthly in-flight magazine featuring articles in English and in Urdu. Flipping through the colourful pages I came across a piece titled ‘Pride of Pakistan’ by someone called Khushboo Aziz. Under a sub-headline, “Pakistan’s National Anthem”, were the somewhat grandiose words:

“Quaid-e-Azam (‘the great leader’ as Jinnah is called) being the visionary that he was knew an anthem would also be needed, not only to be used in official capacity but inspire patriotism in the nation. Since he was secular minded, enlightened, and although very patriotic but not in the least petty Jinnah commissioned a Hindu, Lahore-based writer, Jagan Nath Azad three days before independence to write a national anthem for Pakistan.”

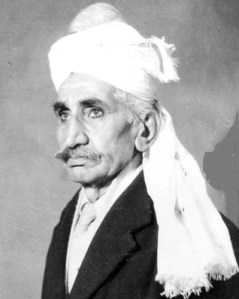

The article included a photo of the poet, with white hair and thick-rimmed glasses, and a solemn expression, and the first stanza of the anthem:

Aé sarzameené paak

Zarray teray haéñ aaj sitaaroñ se taabnaak

Roshan haé kehkashaañ se kaheeñ aaj tayree khaak

Aé sarzameené paak

(O pure land / The stars illuminate each particle of yours / Your very dust is today brighter than a rainbow / O pure land)*.

That was my introduction to an issue that has for me come to symbolise the adhocism that has prevailed in Pakistan, and the polarisation between right-wing zealots and those who want a country based on progressive and liberal, if not secular, values.

The anthem was discontinued some time after Jinnah’s death in September 1948. An official National Anthem Committee (NAC) was formed In December that year. By 1950, there was still no official anthem, but the NAC approved a tune to be played for the Shah of Iran’s impending state visit.

I have a half forgotten childhood memory of my mother’s older brother, the journalist Zawwar Hasan (who came to Pakistan from Allahabad, India, in 1949), laughingly telling us about a reporter friend who visited China in the early 1950s. Asked about Pakistan’s national anthem, too embarrassed to confess that his country didn’t have an offical anthem, the reporter sang some nonsensical rhyme, ‘laralapa laralapa’.

The NAC continued to seek submissions for an official anthem, eventually selecting Jallandari’s lyrics from among 723 entries, in 1952. Jallandari was a member of the National Anthem Committee, but questions about a possible conflict of interest seem to have arisen.

The Humsafar article termed Azad’s song as “the anthem for Pakistan’s Muslims,” apparently forgetting about the country’s non-Muslim citizens. Even after the forced migrations on either side, in the early years, West Pakistan still had a 10 per cent non-Muslim population, and East Pakistan about 25 per cent. Pakistan’s non-Muslim population is symbolised by the white stripe in Pakistan’s flag (this design element is often overlooked but those who think about it see it as a critical piece of symbolism, the essential part that attaches the flag to the pole; others rudely refer to it as being the place to shove the flagpole through).

The article provided no references, but searching the Internet later I found a front page article in India’s respected daily The Hindu, headlined: ‘A Hindu wrote Pakistan’s first national anthem’, by Luv Puri, a Kashmiri journalist. ‘How Jinnah got Urdu-knowing Jagannath Azad to write the song,’ read the introduction (June 19, 2005).

“As the debate about Jinnah’s secular August 1947 vision of his country rages on, this little known fact will be of public interest,” wrote Puri, after the opening stanza of the anthem (also quoted in the Humsafar article).

The article drew from an interview of Azad by Puri shortly before the poet passed away, aged 85, on July 24, 2004. Movingly titled “My last wish is to write a song of peace for both India & Pakistan: Azad”, the interview was published in the website of Milli Gazette (New Delhi, Aug 16-31, 2004). It focused on Azad’s role as the author of Pakistan’s first national anthem, which “gives him a special place” in Pakistan’s history, said the brief introduction.

Sadly, Puri’s assumption that Azad occupies a ‘special place’ in Pakistan’s history is a trifle misplaced in a country that has not officially acknowledged Azad’s contributions, even to Urdu, and his study of the official poet Allama Iqbal’s works. Although the literary circles in Pakistan have always held Azad in high esteem, but there are those who refuse to credit him as the author of the country’s first anthem, and there appears to be little place for him in Pakistan’s official narrative or public discourse.

Talking to Puri in 2004, Azad explained how he came to write the anthem (or ‘tarana’): “In August, 1947 when mayhem had struck the whole Indian subcontinent I was in Lahore where I was working in a literary newspaper. All my relatives had left for India and for me to think of leaving Lahore was painful. I decided to stay on for some time and take a chance by staying back. Even my Muslim friends requested me to stay on and took responsibility of my safety.

“On the morning of August 9, 1947, there was a message from Pakistan’s first Governor-General, Mohammad Ali Jinnah. It was through a friend working in Radio Lahore who called me to his office. He told me ‘Quaid-e-Azam wants you to write a national anthem for Pakistan’. I told them it would be difficult to pen it in five days and my friend pleaded that as the request has come from the tallest leader of Pakistan, I should consider his request. On much persistence, I agreed.”

Why him? Azad said he believed the answer to this question lay in Jinnah’s Aug 11, 1947 speech to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan in Karachi, in which he stressed that all Pakistanis would be equal citizens of the state, regardless of religion:

“You are free, you are free to go to your temples. You are free to go to your mosques or any other place of worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed. That has nothing to do with the business of the state…

“We are starting in the days when there is no discrimination, no distinction between one community and another. We are starting with this fundamental principle that we are all citizens and equal citizens of one State…

“I think you should keep that in front of us as our ideal, and you will find that in the course of time Hindus will cease to be Hindus and Muslims will cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense, as citizens of the State.”

“It is for historians and analysts to judge what made Jinnah sahib to make this speech,” said Azad. “But clearly as understood by the speech was the fact he wanted to create a secular Pakistan, despite the fact the whole continent particularly the Punjab province had seen a human tragedy in the form of communal massacres.”

He added: “Even I was surprised when my colleagues in Radio Pakistan, Lahore approached me that Jinnah sahib wanted me to write Pakistan’s national anthem.” Asked why, they said that Mr Jinnah wanted the anthem to be written by an ‘Urdu-knowing Hindu’. If this was so, it was an attempt to change the common perception of Urdu being a “Muslim” language and Hindi and Sanskrit as “Hindu”. For the generations that grew up before Partition, these divisions weren’t as strong. Azad’s father, Tilok Chand Mehroom was himself a not only a well-known Urdu poet but also a noted ‘naat khwan’, musically reciting Islamic religious poetry at gatherings

“I believe Jinnah sahib wanted to sow the roots of secularism in a Pakistan where intolerance had no place,” said Azad.

He told Puri that he wrote the anthem in five days, and Jinnah approved it within hours. However, Azad himself was forced to leave for India a few months after Independence, a decision that was most painful for him. “The situation in both east and west Punjab was becoming worse with every passing day,” he told Puri. His friends who in September 1947 had asked him to stay felt that even they would not be able to protect him as emotions ran high. Many Hindus sought shelter in refugee camps, and Azad felt compelled to join them.

“I had not intended to leave Lahore in a hurry – in fact I wanted to stay there permanently. It so happened that where I lived was a predominantly Hindu area and the Hindus has started to vacate it when the troubles started,” he writes in his memoirs ‘AnkheiN TarastiN HaiN‘ — My Eyes Thirst (1981).

“A few of us had decided that we will not leave our homes and our country but every morning brought news of people who had not been able to stick to this decision and the number of these decision-makers was reducing day by day. One day I realised that I was the only remaining Hindu out of the 60,000 population – everyone had left. It was in such atmosphere that I heard my Pakistan anthem being broadcast by Radio Lahore on the night of 14 August 1947.”

He also talks about this broadcast in a footnote in his book Hayat-e-Mehroom (1987), that I came across recently on the Jagganath Azad website – http://www.jagannathazad.info).

The footnote contains a startling reference to an anthem by Jallandari broadcast in India the following day. “When Radio Pakistan (Lahore) made the announcement of the founding of Pakistan that night, it was followed by a broadcast of my National Anthem ‘Zarre tere hein aaj sitaaron se taabnaak, Ai sarzameen-e-Pak’. The other side of this image is that on the next day, 15 August 1947 – when India was celebrating its independence – Hafeez Jalandhari’s anthem ‘Ai watan, Ai India, Ai Bharat, Ai Hindustan’ was broadcast by All India Radio (Delhi)”.

Azad’s 1981 memoir includes a profoundly moving account of his departure from his beloved Lahore. The bus full of refugees he was in, bound for the city of Amritsar across the new border, stopped briefly near the grandly colonial Municipal Corporation building in the heart of the city. Looking out the window, Azad saw ‘Maulana’ (Salahuddin Ahmed) “standing at a street corner, gazing numbly at the buses and trucks packed with refugees headed out of Lahore”. (Ahmed, a member of Lahore’s literary circles, was the maternal grandfather of the well known lawyers, sisters Asma Jahangir and Hina Jillani).

“Suddenly his eyes fell upon me and he ran towards the bus. He wanted to say something to me but the words caught in his throat and his eyes grew moist. I did not say anything either. The bus departed and we were left gazing in each other’s direction.”

The well-known writer Zahida Hina, who knew him personally, cites this account in her obituary of Azad published in Urdu daily Jang in August 2004, liltingly titled ‘Maut chahe bhi tau naam uss ka mitta sakti nahin’ (Death, even if it wants, cannot erase his name). Paying tribute to him, she comments on the tragedy of the man who wrote Pakistan’s first national anthem at such short notice, in compliance with the wishes of the country’s founder, being forced to leave his homeland.

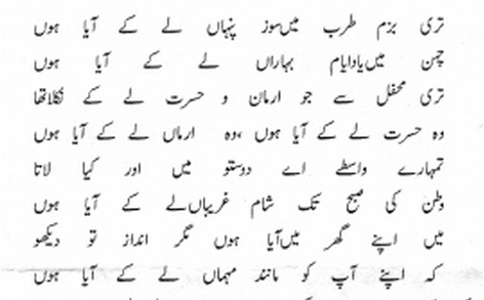

Azad visited Pakistan often for literary events and meetings, and was always received warmly and enthusiastically by Pakistani writers and poets. But his pain at returning to his ‘homeland’ as a ‘guest’ was tangible, and is reflected in the poem he spontaneously recited on returning for the first time for a literary event.

Tumhare wastey ae doston mein aur kya lata

Watan ki subh tak sham-e-ghareeban le ke aya hoon

Mein apne ghar mein aya hoon magar andaz tau dekho

Ke apne aap ko manind mehman le ke aya hoon

(What else could I bring for you, O friends,

To the dawn of this country I bring the mourning of night

I have come to my own home but look at how I’ve come

That I have brought myself here as if I’m a guest)

In India, Azad’s knowledge of Urdu and his expertise on Allama Iqbal – Pakistan’s national poet who is credited with first articulating the need for a ‘separate Muslim nation’ — were not at a premium either but he stuck to his guns. Despite working in a government position, he took up cudgels on against the right-wing lobby that tried to undermine the status of Iqbal in India. He was also an outspoken critic of attacks on Muslims in India.

But Azad’s secular, non-communal vision, his love for Pakistan, for Urdu and for Iqbal, have mattered little in the official discourse of the land he was forced to leave. His departure from Pakistan and Jinnah’s death paved the way for the anthem to be scrapped. “Hidden hands” as the late respected press chronicler Zamir Niazi put it, literally censored Jinnah’s progressive, secular views from the public eye. Jinnah’s August 11, 1947 speech was never included in school textbooks or broadcast on the radio. The battle of ideologies in Pakistan includes making public this forgotten narrative.

Perhaps my ignorance about Azad and his anthem can be excused given that it has been invisible from the public view for so long. Few people outside the literary circles knew about it, even journalists like my uncle and his friend who sang the nonsense verses in China.

After my op-ed ‘Another time, another anthem’ was published (Dawn, September 19, 2009), I felt even more foolish when I learnt that so many people I know were familiar with this narrative. One of them was the elderly peace activist and former minister Dr Mubashir Hasan in Lahore who sent me a copy of Zahida Hina’s 2004 obituary of Azad. He had got it from the former newspaper editor and activist I.A. Rehman who heads the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan. Rehman Sahib later told me that he came to Pakistan in Nov 1947 and remembers Radio Pakistan playing it.

Another friend, Zaheer Alam Kidvai, who introduced Macintosh computers to Pakistan in the 1980s had written a brief blog post about Azad’s anthem in May 2009, that I saw only later, in which he quoted the first stanza of Azad’s poem, the only lines he could recall. He remembered the “majestic sound” of the anthem and lamented the disappearance of the “richness of the band due so much to the sounds of the instruments of that time, as well as the chorus version”.

He finds the current anthem “rather martial and ‘glorious’ in a colonial kind of way … which is how people steeped in nationalism would like it to be.”

“People steeped in nationalism” also rather vehemently oppose the notion that the current anthem had a predecessor. In the current climate of hyper-nationalism, those who assert the alternative narrative, or critique the current national anthem, evoke some rather vicious responses.

The ‘Azad anthem’ narrative relies on word of mouth and memories rather than any hard evidence. The state-owned Radio Pakistan has no record of Azad’s anthem, as the current Director General of Radio Pakistan, Murtaza Solangi found when he tried to plan a special feature on Azad in 2010. Had it been some regular bureaucrat, I might have been sceptical of his efforts. But I’ve known Murtaza since the 1980s when we were both part of an activist theatre group called Dastak in Karachi. I know him to be a committed and sincere person, as well as a meticulous researcher and journalist. He has modernised Radio Pakistan, brought it into the digital age, and is getting old archives uploaded to the Internet in an effort to make Pakistan’s history accessible to the public.

In this spirit, he directed his staff to find Mr Jinnah’s speech of August 11, 1947, only to learn that this too was missing. The BBC and All India Radio (AIR) have also been unable find it in their archives. (‘India says it does not have Jinnah’s 1947 speech’, BBC, 8 June 2012).

“This speech is very important for people who want to direct Pakistan to the goal of a modern, pluralistic, democratic state,” says Murtaza. “Unfortunately in 1947, radio stations in what is now Pakistan did not have proper recording facilities, so they don’t have a copy of the historic speech.”

“Jinnah sahib’s Aug 11, 1947 speech was practically censored during his lifetime. Had those people succeeded, there would be people now saying that he never made that speech,” Zahida Hina told me when I rang her after reading her obituary on Azad. “Just because there are no official records, does not prove anything – many well known and respected figures remember hearing this anthem on Radio Pakistan. In the absence of a record, it’s Azad’s word and their’s, against anyone else’s.”

I tried to apologise to her, embarrassed by my ignorance but she brushed it aside with a laugh, saying, “I was just telling someone that we Urdu writers can slog away but it’s only when someone writes the same thing in English that people take note.”

She is right, of course. Her observation stems from the status of English compared to the local languages in Pakistan – English is still the language of power in this former British colony.

“There are people you know are truthful,” she added. “Jagannath Azad was not a liar. If he says he wrote this tarana (anthem) for Pakistan, at the behest of Mr Jinnah, I believe him. If there are people who choose not to believe him because there is no ‘evidence’, then that is their choice.”

After reading an article in 2010 focusing on the controversy of Azad’s Pakistan anthem, Ilmana Fasih, an Indian doctor and blogger was reminded of an incident that took place in the mid-1970s when she was a little girl growing up in the residential compound of the Kashmir University Campus in Srinagar.

Jagannath Azad was a friend of her father’s and would often visit their home. She remembers him as “a man of few words, and whenever he spoke, it was mostly Urdu shayari (poetry). He was an extremely humble man too”. One day, he was over, reciting his poems before a small gathering that included the leading Indian writer and political commentator Balraj Puri. Young Ilmana barged into the room with some complaint about her brother, interrupting the poetry recital. Scolded roundly by her father in front of all the guests, she began to cry.

“In order to diffuse the embarrassment, Uncle Azad (as we called him), called me near him and in chaste Urdu tried to explain to me, ‘Beti, aise guftugu ke darmiyan bolna, dakhl dar maqoolat kehlata hai’ (Child, to interrupt such a discussion is termed as interference of your elders).

“I was barely seven or eight years old, I did not even get a tenth of what he was saying. And instead of heeding his advice, in a tearful state, I almost mindlessly fired another silly question, ‘Uncle, how come you know such hard Urdu?’”

What she meant, without saying so in as many words was that, “Uncle you aren’t even a Muslim, then how come you speak such good Urdu?”

Azad smiled in response to Ilmana’s implied question and her father tried to salvage the situation by saying: “You know this uncle has written the national anthem of Pakistan.”

The smile became sad and Azad looked down as tears flooded his eyes, remembers Ilmana. “My father got up and gave him a hug. I ran out of the room again playing, without realising the significance of the information my father had given me, until just a few months ago when I read an article about the controversy around the national anthem.”

Balraj Puri wrote in his obituary about Azad: “We often debated the possible impact on Pakistan’s make-up and its relations with India if he had remained a citizen of Pakistan and enjoyed a respectable status there… He would often become nostalgic about the possibility. The very fact that it was he who was asked to write the first national anthem of Pakistan within less than a week before its formal birth indicates the potentiality of its happening.” (Milli Gazette, 16-31 Aug 2004)

So, clearly, Azad’s achievement was no secret among literary circles. He referred to the anthem and how he came to write it, in various interviews and on his visits to Pakistan, as well as in his 1981 memoirs. No one challenged his account during his lifetime. It was only after the narrative reached the mainstream media in Pakistan following his death in 2004, that some people – those “steeped in nationalism” – began to contradict it.

“I trust my memory, my ears and the uprightness of the Uncle Azad I knew,” writes Ilmana. “People who draw conclusions about the history written in Pakistan, do they have an answer to the question: Why did the National Anthem Committee wait three months after the demise of Quaid-e-Azam, and not in his lifetime, to come up with the quest for a new anthem?”

We now have access to Azad’s complete anthem rather than the first few stanzas quoted in various articles. His son Chander K. Azad emailed me a scanned copy — which he himself could not read as it is in the Urdu script. (‘Chiragh taley andhera’, he commented wryly in his accompanying email – under the lamp, darkness). I’ve posted the complete poem, with a transliteration and translation, to my blog and it is now also available on other websites and blogs, including the Jagannath Azad website that has since been developed.

There is no doubt that Azad wrote this anthem. What is disputed, in the absence of hard evidence, is whether Jinnah commissioned the anthem, whether it was the official national anthem of Pakistan from August 14, 1947 to December 1948, and whether Radio Pakistan broadcast it – although there are people living who remember hearing it.

None of this takes away from the fact that Azad did write a nationalist poem for Pakistan. Even if details of how it came to be written cannot be proved, why discard it? This is not to denigrate the official anthem by Hafeez Jallandari but to re-introduce another beautiful anthem on merit. It shouldn’t matter who the writer was, although the fact that he was such a distinguished poet as well as an authority on Pakistan’s national poet Iqbal, should go in his favour. There are many nationalist songs that Pakistanis love, own and sing besides the national anthem. Why not add Azad’s anthem to the repertoire? No one is advocating that it replace the present national anthem, but it should at least be acknowledged and taught to school children. Owning these lyrics would go a long way towards bridging the divide that has been created between Hindu and Muslim and by extension, between India and Pakistan.

“Every new nation has to go through the process of nation building and Pakistan is no exception,” said Azad in his last interview to Luv Puri. “But the fact remains both India and Pakistan remain bonded to a centuries’ old heritage, which cannot be broken so easily. No matter what happens, I believe the natural bonds between the two countries would continue to exist.

“As a person who has got the love and affection of both Indians and Pakistanis, it would be my last wish to bring the two nations together. As a poet, I want to make a humble contribution by penning a ‘song of peace’ that is common to both countries. It will be sung by millions of Indians and Pakistanis. It is my wish that one day the people of the two countries will sing the songs of love instead of hatred.”

Azad did not live to pen the song he wanted. Reviving his lost anthem could go a long way towards fulfilling his wish for peace between India and Pakistan — and contribute to an alternative discourse incorporating pluralism and diversity.

(ends)

Filed under: Music, Pakistan-India | Tagged: Jagannath Azad, Pakistan anthem, shahvaar ali khan |

Kudos, Beena to you for your perseverence, to Shahvar for not just his talent but his peace vision, and all those who made this possible. I salute them all.

I feel more reassured that whoever envisions a real and lasting peace between India and Pakistan, must keep persevering, till the dream becomes a reality.

We will see that light one day, and hopefully soon :).

LikeLike

[…] people to “Bring back Jagannath Azad’s Pakistan anthem”. Her latest on the issue is here: “65 years… Reviving Jagannath Azad’s poem for Pakistan” . The following is, of course, an appeal by a Pakistani to his compatriots: “Jinnah’s […]

LikeLike

[…] Her latest on the issue is here: “65 years… Reviving Jagannath Azad’s poem for Pakistan” https://beenasarwar.wordpress.com/2012/08/14/65-years-later-reviving-jagannath-azads-poem-pakistan/ […]

LikeLike

[…] Update: 65 years on… Reviving Jagannath Azad’s poem for Pakistan […]

LikeLike